Contravariance and Covariance - Part 2

Josiah Willard Gibbs

Vector Calculus

Vector Concept 2 -- Vector Spaces

In the design of computer languages, the notion of contravariance and covariance

have been borrowed from category theory to facilitate the discussion of type

coercion and signature. Category theory, on the other hand, borrowed and abstracted

the notion of contravariance and covariance from classical tensor analysis which

in turn had its origins in physics.

In keeping with Feynman's observation that it is useful to have different ways thinking about known ideas,

part 2 will be developing vectors from the point of view of linear algebra and vector spaces, which is a branch of algebra.

The axiomatic approach used in algebra requires the introduction of a number of definitions.

However, only the definitions needed to illustrate contravariance and covariance in an abstract vector

space will be given. So, unfortunately, for the sake of brevity, no detailed motivation of these mathematical concepts is going to be provided (*).

Needed Ideas From Linear Algebra

- Vector Space

- Linearly Independent

- Span

- Basis

- Coordinates

- Change of Basis

- Linear Functional

- Dual Space

The definition of a vector space also uses the algebraic concept

of a field. (Not to be confused with a physical field, like, for example,

the gravitational field...same words, different concepts.) For those

who have not studied fields and

do not wish to, good examples are the real numbers R, or the complex numbers C,

which can be substituted in the definition below to allow you to follow

along. Boldface

is used to indicate elements of the vector space, normal font is used to indicate

scalars

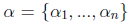

We now introduce some notation, and a convention, that will be useful.

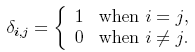

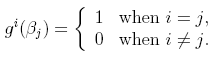

The Kronecker delta is defined by:

Also, the Einstein summation convention will be used.

That is, whenever repeated indices appear in an equation, it is understood that a summation is taken over these

repeated indices.

Also, the Einstein summation convention will be used.

That is, whenever repeated indices appear in an equation, it is understood that a summation is taken over these

repeated indices.

Vector Space

A vector space V consists of a set of objects, called vectors, and a field F, called scalars , and a binary operation + on vectors, that satisfies the following axioms:i) if a and b are vectors, then so is a +b for all vectors a and b

ii) a+ b =b + a

iii) a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c

iv) There is a zero vector, 0, such that 0 + a = a + 0 = a for any vector a

v) There are additive inverses. For each vector a, there exists a vector -a such that a + (-a) = -a + a = 0.

vi) Scalar multiplication. For any scalar k and any vector a, k a is a vector.

vii) k(a + b) = ka + kb

viii) (k + l)a = ka + la for any scalars k and l

ix) k(l(a)) = kl(a) for any scalars k and l

x) 1a = a1 = a where 1 is the scalar identity

Linear Independence

A set of vectors {v1,...,vk} is linearly independent iffa1v1 + ... + akvk = 0 implies a1=...=ak= 0

Span

The span of a set of vectors {v1,...,vk} is the intersection of all subspaces that contain {v1,...,vk}

A straightforward result is that the span of a set of vectors {v1,...,vk}

is given

by all possible linear combinations of the {v1,...,vk}.

This result is often more

useful to work with than the actual definition.

Basis

A basis for a vector space is any set of linearly independent vectors that span V.

Given a basis for V, the number of vectors

in the basis is called the dimension of V. A

finite dimensional

vector space

is a vector space that is spanned by a finite number of vectors.

The discussion will be limited to finite dimensional vector spaces.

Coordinates

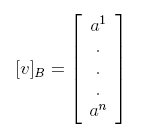

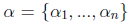

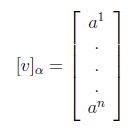

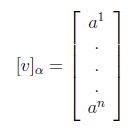

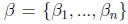

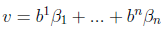

Let v be a vector in V, and let β = {v1,...,vn} be an ordered basis for V. Then if v = a1v1 + ... + anvn , the scalars a1,...,an are called the coordinates of v with respect to the basis β, and is written as a nx1 column matrix:

Change of Basis

We do not wish to be constrained to one basis. If we formulate an equation that uses

coordinates in its formulation, we would like to know that it is true independent

of the basis chosen. Therefore, we need to know how to express our equation in a

new basis. Also, it is often the case that we are able to transform to a new basis

where our equations take on a simpler form. For these reasons, it important to study

the change of basis problem.

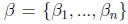

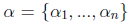

Let

be a basis for V and v be an arbitrary vector with coordinates

be a basis for V and v be an arbitrary vector with coordinates

If we now instead wish to use a different basis

If we now instead wish to use a different basis

how do we calculate the new coordinates?

how do we calculate the new coordinates?

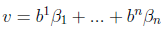

To answer this question, expand v in the beta basis, using the cordinates

just given:

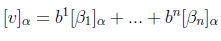

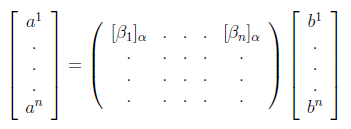

Then, writing this in coordinate form in the alpha basis gives

Then, writing this in coordinate form in the alpha basis gives

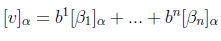

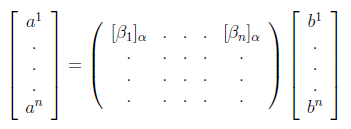

This can be re-written as a nxn matrix times a nx1 matrix as

This can be re-written as a nxn matrix times a nx1 matrix as

where the nxn matrix's columns are the coordinates of the beta basis vectors with respect to the alpha basis. Denoting the nxn matrix, by P, this can be written as

where the nxn matrix's columns are the coordinates of the beta basis vectors with respect to the alpha basis. Denoting the nxn matrix, by P, this can be written as

vα = P vβ

and left multipling by P-1 gives the require expression for the coordinates

of v in the new basis:

vβ = P-1 vα

The matrix P is called the transistion matrix from the α basis to the

β basis.

( A word on convention: if instead of expanding v in the β basis above,

I had expanded v in the α basis, and taken coordinates in the β basis, I would

have finally arrived at a slightly different

form:

vβ = Q vα

where Q is the matrix formed by the coordinate vectors of the α basis

vectors with respect to the β basis. Occasionally, people call Q the

transition matrix. If you are reading a book on linear algebra you need to check

the convention being used.)

Having provided most of the needed definitions, we are very close to having all language needed to state the main idea.

Recall in the "directed arrow" definition of a vector, the contravariant components

of a vector were its coordinates with respect to the reciprocal lattice, and the

reciprocal lattice was defined by the requirement ei.ek = 0. In the abstract vector space formulation, this notion is generalized by the

concept of the dual space and dual basis, which we now introduce.

Linear Functional

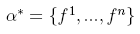

Definition: A linear functional on a vector space V is a linear map from V into the scalars K.Dual Space and Dual Vectors

The set of all linear functionals on a vector space V is called the dual space of V, denoted by V*. Elements of the dual space are called dual vectors .

If V is a vector space of dimension n, then V*

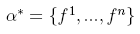

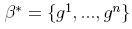

is a vector space of dimension n. Given a basis α for V, we construct

a basis for V* as follows:

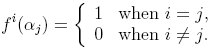

Dual Basis

For a given basis α,

We now know how to get a basis for V* given a basis

for V . This allows us to write the components for an aritrary

dual vector. We now want to enquire how the coordinates of our arbitary dual

vector change when a change of basis is performed is performed in V. The

change of basis induces a change of basis on the dual space.

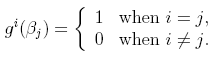

The key to discovering how dual vectors transform is to require that the new dual

basis vectors, gi, satisfy

Let the transformation matrix to the new dual basis be hik .

Then gi=hik fk, where the Einstein summation convention

is used to indicate a summation is taken over the indices k. If βj = Qjlαl

then we have

Let the transformation matrix to the new dual basis be hik .

Then gi=hik fk, where the Einstein summation convention

is used to indicate a summation is taken over the indices k. If βj = Qjlαl

then we have

| Old Bases | New Bases |

|

|

|

|

hik fkQjlα

l

= δij

Using the summation

convention and simplifying this reduces to

hik Qjl

δkl = δij

and simplifying one more time gives

hil Qjl= δij

or in other words

hil QTlj= δij

where QT is the transpose of Q.

Thus we have the important result that

Next week -- Tensor analysis and vector transformation laws.

h = (QT)-1

So, the coordinates in the new dual basis are computed from the change of basis

matrix by taking the transpose inverse of the transformation matrix and using

that as the transformation matrix for the dual vectors. The dual vectors are also

called contravariant vectors, and the vectors in the original space are

called covariant vectors. The contravariant vectors are said to transform

contragrediently and the covariant vectors transform cogrediently.

(*)

Starting with part 2, the discussion becomes more abstract. I cover quickly

what is usually covered at a more leisurely pace in advanced linear algebra coures.

I recommended "Linear Algebra" by Kunze and Hoffman as a reference, and also Schaum's Linear Algebra for

practice problems.

There are other possible reference books (for example, Strang's unfortunate text "Linear Algebra and Its Applications") on linear algebra, but they devote a lot of time

to other topics before even getting to linear transformations, which is the heart of the linear algebra. Kunze and Hoffman is the

standard reference. The problem with Strang is a student can take a linear algebra course using his text, and not understand the centrality

of linear transformations because Strang spends so much time on other, and easier, topics. Solving equations using matrices with either matrix multiplication ,

or Gaussian elimination techniqes, which Strang devotes much time to is rather trivial. In fact, these topics I have successfully taught to a 9 year old.

Vector spaces, basis, and linear transformations is more demanding.

Cogitations on Physics, Math, and Computers

Cogitations on Physics, Math, and Computers